Learning Metacognition as Higher Order Thinking

I have written in the past about the two levels of metacognition with the higher order allowing an individual to use a full suite of higher order thinking skills across any context. How is this kind of thinking achieved?

The initial consideration is to consider the maturity of the brain. Metacognition is about as abstract as it can get: thinking and understanding your own thinking along with an awareness of yourself. Because of the considerable thinking resources necessary for this kind of activity, the pre-frontal areas of the brain must be reasonably well developed. With the significant development of myelination of the frontal areas beginning at the onset of puberty with the massive release of sex hormones, trying to teach full metacognition to pre-pubescent children is akin to trying to teach a three-month-old to walk. Regardless of the admirable intentions, it simply isn’t going to happen. I find it sad that so much energy is expended in primary schools to teach this skill when the time could be so much better used to teach and reinforce basic cognitive skills. I can write this as often as I want, but only a minuscule number of practitioners who believe that this should be done will even consider it.

Lower order metacognitive thinking skills take a couple of well understood learning methods to achieve.

The first is to understand what you know and what you don’t know. This can be quite easily developed. Keep in mind that knowing what you know (or knowing what you don’t know) relies on a feeling that arises when something is considered.

I developed a method of both testing this and developing a person’s recognition of that feeling a number of years ago. The test involved asking general knowledge questions that we knew the subjects would be able to answer correctly about 50% of the time. In addition to asking the subjects to try to correctly answer the questions, we asked them to indicate whether or not they knew the answer or were just guessing. When testing first year university students at a reasonably selective university, we found that about 80% of the students were simply guessing as to whether they knew the answer or were just guessing.

This result was surprising. However, we soon learned that after a number of sessions (about six, one week apart) where they did the task over and over they improved their ability to recognize the feeling of knowing to about 80% correct.

We can easily (and enjoyably) teach people to learn to recognize the feeling of knowing. In fact, we found that this method worked at the older, middle child age (10 – 12).

The foundation for metacognition can be taught.

The next stage in learning metacognitive abilities is the monitoring of thought processes. This involves actively engaging in your own thought processes. Highly abstract and much more difficult than learning to recognize when you know something. By constantly reflecting on our own thought processes, we can develop basic metacognition. This basic recognition helps us to recognize aberrations in our thinking and differing states of health in both our bodies and brains. A powerful higher order thinking skill that allows to monitor ourselves on the inside and harness much of our thinking to deal with challenges that we face in the environment.

This is why I refer to basic metacognition as the most powerful higher order thinking skill that we can acquire.

Using this skill and the other higher order thinking skills still falls prey to the problem of transference. After all, metacognition is something that we learn, and we usually learn things within a given context. The problem of transference is overcome when we use what we have learned across contexts. This means that we need to monitor our thinking in whatever context we are in that requires thinking. Almost every activity we engage in. This is more difficult than simply learning the skill in the first place and takes considerable self-discipline.

Now, after considering the acquisition of basic metacognition and the challenges that this entails, ratcheting it up to the highest level of thinking is far more challenging.

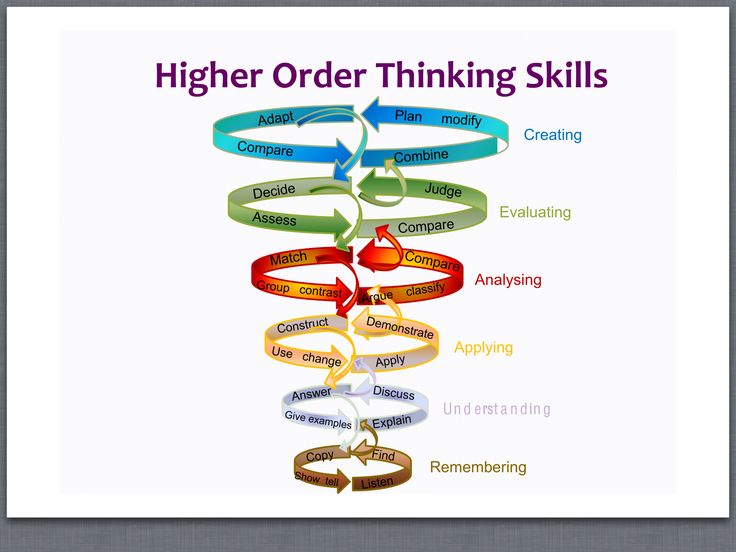

The first thing that is necessary is to acquire a number of the higher-level thinking skills: critical thinking, higher order creativity, complex inductive reasoning, hypothetico-deductive reasoning, higher order reasoning, and higher order logic. This, in and of itself, is a challenge for anyone. It is difficult enough to master one of these skills, but to acquire a full suite is a long-term pursuit. In addition to that, using these skills across a variety of contexts is most difficult.

Besides creativity, by far the most difficult skill to generalize across contexts is the ability to self-correct. Self-correction is rarely seen in the wild. Self-correction occurs when an individual is willing, based on evidence alone, to change their thinking. When was the last time you witnessed an academic, politician, business person, celebrity, ideologue, or anyone else throw their hands in the air and say to the world, “I have been wrong for all this time and am, sincerely, changing the way I think.” Changing direction does not count when it is done simply for the purpose of personal gain (political, business etc.) and is usually not because of evidence.

Self-correction involves the careful weighting of evidence along with the thorough evaluation of the source of the evidence. Because we rely so much on trusted authorities to gain much of our knowledge, we need to be aware of basic research methodology – we have all heard, “Science has proven…” when careful examination of the claim reveals sham, pseudo-scientific methods that are used to promote a belief, idea, or product.

In addition, trusted sources needed to be considered for the presence of biases that taint their messages. If scientific research is sponsored by an organization, the game of trivial pursuit, that is called research today, almost guarantees that the published results are always found to be in favour of the funder – you don’t bite the hand that feeds you.

However, this does not preclude someone from holding irrational beliefs – beliefs that will not stand up to any kind of scrutiny. Such beliefs would include religious beliefs, extreme ideological beliefs, or known pseudo-scientific beliefs (extra-terrestrial kidnappings!). There is nothing wrong with holding these beliefs – I did not say that there is nothing wrong with the beliefs themselves. There is nothing wrong with holding irrational beliefs as long as there is no pretence of rationality and claims about the beliefs are not presented as rational.

Metacognition, in general, is the most powerful thinking skill that we can acquire with the higher of the two types of metacognition setting people apart as someone truly different. Not usually as a “look at me – I’m charismatically special” kind of way, but the kind of special that almost immediately engenders trust and admiration. The kind of person that can be both frightening and brilliant at the same time. This kind of person is rare, even amongst the billions of us.